SOME HISTORY: Robert Rauschenberg and Social and Environmental Activism

By Julie Martin

When Robert Rauschenberg Executive Director Christy MacLear saw some early photos of a meeting in the large space at 381 Lafayette Street, familiarly called the Chapel, she recognized it as the same room that had held the 2012 planning session for the upcoming Marfa Dialogues/NY. Soon after, she contacted me wanting to know more about the images, and asked me to write about some of the events and projects that resulted from Rauschenberg’s involvement in and commitment to issues affecting both the individual and the common good that today is manifest in the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation and — this year — in Marfa Dialogues/NY.

The Chapel, as we called it back then, was actually half a chapel that was attached to the building that Bob bought in 1965, a former orphanage, whose place of worship had been cut in half, with the resulting empty space leased to a parking lot. Not only did it function as Rauschenberg’s studio for several years, but it was the site of important announcements of projects that testify to his involvement in projects that went beyond art-making into the realms of social concern. In particular the Chapel played an symbolic role in his work with the foundation Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.).

Several strands of activities came together in the founding of Experiments in Art and Technology. It began in 1960 when Rauschenberg met Swedish research engineer Billy Klüver in the garden of the Museum of Modern Art in New York, where Klüver was working with Swiss artist Jean Tinguely on Homage to New York, a large meta-matic drawing machine that was going to destroy itself during its performance. Always interested in collaborating, Rauschenberg contributed a work called Money Thrower to Homage to New York. As Klüver later described it in Art in America:

Tinguely had asked people to contribute things to the machine and on the day of the performance, March 17, Rauschenberg showed up with a “mascot” for the machine which he called Money Thrower. It consisted of a small rectangular open metal box 2 1/2 x 4 x 10 inches which had heating element wires at the bottom of the box on which Rauschenberg had put gun powder. At each end of the top of the box was fastened a large spiral binding coil. The ends of the two coils were bent together and intertwined so they remained stationary. In the coils Rauschenberg had inserted 12 silver dollars. When the circuit was closed, the gun powder would ignite and free the coils from each other, flinging the coins into the audience as they sprang apart. Rauschenberg’s gunpowder exploded in the 7th minute of the machine’s self-destruction and the silver dollars were never found again. (Klüver, Billy with Julie Martin. “Four Difficult Pieces.” Art in America, July 1991)

Robert Rauschenberg, Money Thrower, 1960

Collection Moderna Museet

© Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

ORACLE: AN ENVIRONMENTAL SOUND SCULPTURE

Soon after Homage to New York Klüver asked Rauschenberg if he had any ideas they could work on together. Klüver recalled, ”He asked me if it was possible to make an interactive environment, where the temperature, sound, smell, lights etc. could be affected by the person who moved through it. I began thinking about some possibilities, but … it proved impossible to achieve his original ideas for a multi-responsive environment.” (Ibid.) Rauschenberg then focused on a five part painting in which a radio would be located behind each panel and a viewer would be able to change the volume and speed of scanning between stations from a control console in front of the work. His idea was for a wireless control console and for the radios and to use the AM band, which was more varied and lively in those days. According to Klüver …

Harold Hodges and I began work on a design where all five AM radios were mounted in a control console in front of the paintings. The speakers on the AM radios would be removed; and the output from each radio would be retransmitted by small AM transmitters to receivers, amplifiers and speakers mounted behind each painting. But the homemade AM transmitters that we built were unstable and operated on such a broad frequency band that they interfered with one another and generated a nightmare of noise. We quickly realized there was no way we could save this system. …(Ibid.)

At the end of 1962, Rauschenberg told me he was now thinking of our project as a five-piece sculpture. One of the pieces would be a staircase on which the “conductor” could sit and control the sound. He asked us to build the staircase to his specifications and he would take care of the other four pieces.

Harold Hodges and Rauschenberg at work on Oracle.

Photo Billy Klüver

We worked on the technical equipment for Oracle for about three years before it was finished. Harold Hodges built two complete systems which had to be discarded as technically unsatisfactory. The third and last system in which the AM signals from the radios were transmitted using empty spots in the FM band, was built when the technology caught up with us at the end of 1964 and we found one of the first crystal-controlled fully transistorized wireless microphone systems, the Comrex system. We immediately bought four systems operating at four different factory-set FM frequencies. Now all we had to do was feed the signals from the AM radios into the FM Comrex transmitters and they would be sent wirelessly to amplifiers and speakers in each of the other four pieces.

Oracle at Leo Castelli Gallery, 1965 photo Rudy Burckhardt

Collection Centre Georges Pompidou

© Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Oracle was shown at Leo Castelli Gallery, opening May 15, 1965. Klüver described it thusly:

In full operation, Oracle becomes an animated cityscape. The sculptures, using materials discarded from buildings and discovered on the sidewalks, are themselves as varied as sights from a busy city street. Since the units can be placed anywhere in relation to one other, any arrangement of the sculpture pieces in a room, leaves open the possibility of another arrangement. The sound too can be “rearranged” in ever changing bits of music, talk, and noise, loud, soft, clear or full of static. The sound from the five radios comes to you as it would on the streets of a city neighborhood on a hot summer day. To this is added the only constant in the piece, the rushing sound of water from the fountain. Oracle has no fixed visual or aural shape, but presents an open invitation to walk in. When you do, the experience is as changing and provocative as the city it is reporting on. (Klüver, Ibid.)

As Klüver worked with more artists in the early ’60s, he began to think broadly about the implications of his experiences and to develop his ideas on the importance for the artists to be able to work with quickly evolving technology; the need to get his colleagues in the engineering community involved with artists, and the value that working with artists could have for engineers in their own work.

By 1966 I had as an engineer worked with Jasper Johns, John Cage, Bob Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, Yvonne Rainer and others. I felt the growing need and interest in using the new technology on the part of the artist, and I knew from my own experience that scientists and engineers could get seriously involved with artists. Some of my first ideas were that engineers were material for the artists; that we were as useful to them as any other material they might use in the realization of an idea. …

Robert Rauschenberg and I were in his kitchen discussing these ideas. He insisted that artists and engineers must work together on a one-to-one basis. Creating something new is the goal of an artist, and Bob knew instinctively that in working with an engineer or scientist a one-to-one collaboration was the only way to do get this done. As soon as he said it I knew that he was right. (Klüver, unpublished notes)

At the time of these conversations on the ideas of artist-engineer collaborations, an opportunity arose to put them into practice. An invitation from Sweden at the beginning of 1966 to participate in a Festival of Art and Technology was the catalyst for Klüver and Rauschenberg to launch a large-scale collaboration between10 New York artists – Rauschenberg with John Cage, Lucinda Childs, Oyvind Fahlström, Alex Hay, Deborah Hay, Steve Paxton, Yvonne Rainer, David, Tudor, Robert Whitman – and more than 30 engineers from Bell Telephone Laboratories to create performances that incorporated the new technology. The artists and engineers had worked together for more than seven months when the trip to Sweden fell though and, in true American style, they decided to hold the performances in New York. They found the 69th Regiment Armory at 25th Street and Lexington Avenue, and with the help of Senator Jacob Javits, a long-time supporter of the arts, obtained the Armory for a two week period in October that year. They began the final plans for the performances that they called 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering. This brings us to the first event that took place in the Chapel, the building Rauschenberg had just recently moved into which was to be his home and studio for the next several years.

On September 29, 1966, the artists and engineers held a “press briefing” on the 9 Evenings that would take place October 13 – 23, 1966 at the 69th Regiment Armory, home of the original 1913 Armory Show. The press conference was held in the Chapel.

Invitation to the Press Briefing on 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering, 1966.

Courtesy E.A.T. Archives

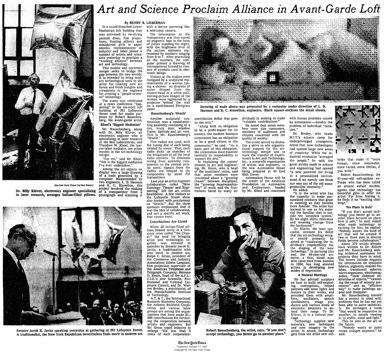

9 Evenings was highly publicized and the press briefing was well attended. Fred McDarrah covered the event for The Village Voice, and an article on Rauschenberg appeared in The New York Times Magazine on October 9, with the title “The Artist as Playwright and Engineer,” featuring the plans for the 9 Evenings.

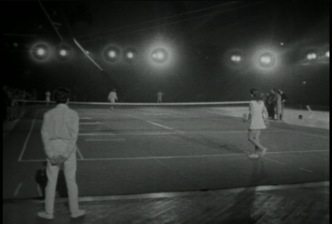

9 Evenings took place at the Armory from October 13 to 23, 1966. The event was widely publicized, and more than 10,000 people attended the performances over the nine evenings, where each artist presented his or her work twice

Robert Rauschenberg, Open Score, 9 Evenings: Theatre & Engineering,

Frame Grab from 16 mm film. Courtesy E.A.T. Archives

The foundation Experiments in Art and Technology was founded soon after the artists and engineers decided to hold the performances in New York, and was officially incorporated on September 26, 1966. The founders were two artists, Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman, and two engineers, Billy Klüver and Fred Waldhauer, colleagues at Bell Telephone Laboratories in Murray Hill, New Jersey. The impetus was the shared experiences they had had working on 9 Evenings. The general feeling shared by all the artists and engineers working on 9 Evenings was that the technical equipment developed for the performances should be shared with other artists, and perhaps even more importantly, that the positive experiences they had working together should be made available to a larger group of artists and engineers.

In November 1966 the artists and engineers who had participated in 9 Evenings held a meeting at the Broadway Central Hotel for artists in New York City to explore possible artists’ interest in using the new technology. It was attended by 300 artists, engineers and other interested people. The reaction was positive to the idea of E.A.T. providing the artists with access to the technical world. Membership was opened to all artists and engineers, and an office was established in a loft at 9 East 16th Street in New York.

There was an immediate response to E.A.T. from artists and the art community. However, much of the early activities of E.A.T. were focused on reaching out to the engineering community and recruiting engineers and scientists who wanted to work with artists. These efforts were very successful and by 1968 E.A.T. had approximately 2000 artist members with 2000 engineers and scientists members signed on to help with their projects. A matching system was developed, through which any artist who contacted E.A.T. with a technical question or project would be matched with an engineer who could work with him or her on the project.

At the basis of E.A.T. is the shared belief of the founders in the value of individual commitment to his or her practice and their taking full responsibility for the work. The means of implementing these ideas in the artist-engineer relationship was through a one-to-one collaboration between the artist and engineer or scientist. While the initial request would come from the artist who wanted to make a work of art, the ideal collaboration would be one in which the two people would each work in their own professional capacity and that the final result would be something that neither of them had totally envisioned when they started. These ideas were articulated in the second newsletter E.A.T.:

Which now brings me to the third photograph taken in the Chapel and to Theodore Kheel, a lawyer and labor mediator who played a key role in reaching resolutions of teacher, subway strikes in New York City in the 1960s and in particular, the 114-day long 1962-63 New York City newspaper strike. Kheel was introduced to Rauschenberg and Klüver by collector John Powers, and Ted readily joined the board of E.A.T.

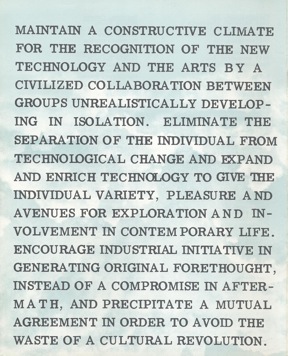

The founders of E.A.T. saw the organization acting as a catalyst to stimulate the involvement of industry and technology with the arts. E.A.T. worked to develop an effective collaborations between artists and engineers with industrial cooperation and sponsorship. To this Kheel added the idea of the labor and political communities. He soon suggested the idea of a press conference to announce the partnerships that E.A.T. hoped to build, not only between artists and engineers and scientists, but with industry, labor and political figures with the goal of realizing artists’ projects. In preparation for the press conference, Rauschenberg and Klüver drafted what they called E.A.T. Aims and printed them on a background of blue sky with clouds.

E.A.T. Aims, 1967. Courtesy E.A.T. Archives

Envelope/Invitation to the E.A.T. press conference, October 10, 1967. Courtesy E.A.T. Archives

The press conference was held at Rauschenberg’s building and included a one day exhibition of 15 works of art incorporating technology in addition to a presentation in the Chapel, with speakers that included Senator Jacob Javits; John Pierce, Executive Director, Communication Sciences Division, Bell Telephone Laboratories; Herman Kenin, President, American Federation of Musicians; Warren Brody, MIT Science Camp; Ralph Gross, President, Commerce and Industry Association; and artist Robert Morris.

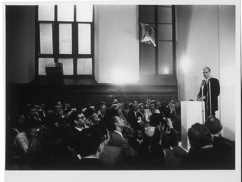

John Pierce, Executive Director, Communication Sciences Division, Bell Telephone Laboratories, speaks at the E.A.T. Press Conference, October 10 1967

Courtesy E.A.T. Archives

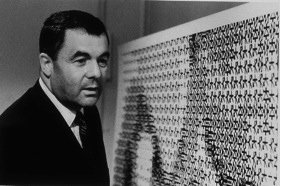

Theodore Kheel at the exhibition accompanying the E.A.T. press conference

Courtesy E.A.T. Archives

Rauschenberg, Marion Javits, Senator Jacob Javits and Billy Klüver with Rauschenberg’s Oracle at the exhibition accompanying the E.A.T. press conference

Courtesy E.A.T. Archives

The press conference was very successful, according to Klüver “I remember Bob and me having dinner at Max’s Kansas City waiting for the morning edition of The New York Times. Not only did our story appear on the first page of the second section, but in the all important placement “above the fold..” (Unpublished lecture)

—————————————————————————————

The second installment of Julie Martin’s essay will be published next week here on marfadialogues.org.